|

|

3 X 3: New Media Fix(es) on Turbulence

|

|

|

turbulence: turbulence:

remixes + bonus beats |

|

|

turbulence: remix + bonus beat turbulence: remix + bonus beat |

|

turbulence: remezclas + bonus beats turbulence: remezclas + bonus beats |

|

| by Eduardo Navas | Edited by Jo-Anne Green, Helen Thorington |

|

|

|

Turbulence turns ten years old in 2006; this means that it now offers an impressive archive of Internet based art. During its first decade, Turbulence became important in the history of a still emerging art form often referenced as new media art.

Turbulence is also part of the history of remix culture. Generally speaking, remix culture can be defined as the global activity consisting of the creative and efficient exchange of information made possible by digital technologies that is supported by the practice of cut/copy and paste. (1) The concept of Remix often referenced in popular culture derives from the model of music remixes which were produced around the late 1960s and early 1970s in New York City with roots in Jamaican music. (2) Today, Remix (the activity of taking samples from pre-existing materials to combine them into new forms according to personal taste) has been extended to other areas of culture, including the visual arts; it plays a vital role in mass communication, especially on the Internet-and in this case, in the Turbulence archive.

The focus in this text is to understand how Turbulence contributes to Remix as a cultural activity, as well as to the history of new media. I will first look at Turbulence as an archive, a type of recording (a vinyl record), and examine in detail selected works according to my theory of Remix. I will then reflect on the aesthetics of Internet art, and its historical importance.

|

Friederike Paetzold | Grey Area | 2002

|

|

| turbulence: nothing but a remix |

|

turbulence: nient'altro che remix turbulence: nient'altro che remix |

|

turbulence: nada más que un remix turbulence: nada más que un remix |

|

Turbulence turns ten at a time that follows, but is somewhat distant from the postmodern: a moment when grand narratives were questioned, and little narratives were favored. (3) The postmodern period, which roughly ranges from the mid/late-sixties to the mid-eighties, was understood as one of fragmentation, bits and pieces, incompleteness and open-ended possibilities.

During the postmodern period, the concept of the music remix was developed. The remix in music was created and defined by the DJs in the nineteen seventies in New York City, Chicago and other parts of the east coast, who re-combined or extended preexisting songs to make them more danceable. Their mixes actually have roots in "toasting," and dub music of Jamaica. (4) The activity of the east coast DJ's evolved into sampling bits of music in the sound studio, which means that the DJ producers were cutting/copying and pasting pre-recorded material to create their own music compositions. Cut/copy and paste, the fragmentation of material, is today part of everyday activities both at work and at home thanks to the computer, and are commonly found in popular software applications, such as Adobe Photoshop and Microsoft Word.

The Internet also depends on sampling, on cut/copy and paste in order to function as a network. File sharing, downloading open source software, live streaming of video and audio, sending and receiving e-mails are but a few of the activities that rely on copying, and deleting (cutting) information from one point to another as data packets. This means that cut/copy and paste is a pivotal element of Internet based art, and apply directly to the Turbulence archive.

What is particular to Internet art is that the user plays a crucial role in activating the work, like the DJ does when s/he plays with vinyl records. The Internet user manipulates the files in the Turbulence archive in the same way the DJ manipulates the record on the turntable. Both access pre-recorded material. The seventies DJ, however, was following the tradition of hackers, because s/he was manipulating records on a machine that was originally used for passive listening. This active interaction with pre-recorded material became part of the mainstream, and we can see how the online user falls within a category in part deriving from the DJ; the user now is expected to play with the files (like a DJ with records) and not just listen or view them passively, because interaction, touching, or in the case of the online user, clicking, is now integrated into culture.

The DJ manipulates a record and the Internet user manipulates the Turbulence archives. Metaphorically then, we can think of the Turbulence archive as a record, and like a "vinyl recording," it can develop scratches, and indeed it has, especially when we consider early works such as Not Walls (1996) by Laurel Wilson which uses Apple's Quickdraw, (5) an online interface that remixes image and text in a 3-D environment. The online work cannot be viewed because the plug-in is no longer available and the work has thus turned into an unplayable or scratched section in Turbulence's record groove.

Thinking of Turbulence as a vinyl record with a few unplayable tracks, this essay will now focus on specific projects which, as we "listen" to them, may show a few scratches of their own.

|

| literature: remixed as internet art |

|

letteratura: remixata come arte in rete letteratura: remixata come arte in rete |

|

literatura: remezclada como arte en internet literatura: remezclada como arte en internet |

|

In later sections a detailed theory of Remix will be given. At this moment what is crucial to understand in order to examine selected projects in the Turbulence archive is the concept of allegory, which is Remix's most vital element. Allegory is a cultural code that new media art, and more specifically Internet art, have inherited from the postmodern. (6)

The remix is always allegorical following the postmodern theories of Craig Owens, who argues that in postmodernism a deconstruction, a transparent awareness of the history and politics behind the object of art is always made present as a "preoccupation with reading." (7) Meaning that the object of contemplation, in our case Remix, depends on recognition (reading) of a pre-existing text (or cultural code). The audience is always expected to see within the work of art its history. This was not so in early modernism, where the work of art suspended its historical code, and the reader could not be held responsible for acknowledging the politics that made the object of art "art." (8) Postmodernism, in effect, remixed modernism to expose how art is defined by ideologies, and histories that are constantly revised. The contemporary artwork is a conceptual and formal collage of previous ideologies, critical philosophies, and formal artistic investigations extended to new media and Internet art.

Internet based art is inherently allegorical; it always relies on pre-existing material to gain authority. The works in Turbulence in this sense are allegorical; they are citations that rely on the authority of previous material that has been copied/cut and pasted, both conceptually and formally. This allegorical impulse, which carries a strong trace of postmodernism is apparent in all the Turbulence commissions. And not surprisingly the medium that is most allegorized is Literature and its narrative strategies; this is particularly true during the early years. Let us begin our examination with Literature and narratives. This focus will then expose other allegories.

|

Marianne Petit with John Neilson | The Grimm Tale | 1996

|

|

Literature is an inspiration, if not the foundation, of many of the works commissioned between 1996 and 1998. Such works include The Grimm Tale by Marianne Petit with John Neilson, (9) North Country: Part 1 by Helen Thorington and Eric Schefter, (10) The Sad Hungarian by Nick Didkovsky and Tom Marsan, (11) and The Story of X by a Russian author. (12)

The Grimm Tale is a story about a boy who is not able to understand the concept "to shudder." This alienates the boy who is misunderstood by those around him. When he finally is able to understand the meaning of the verb, it is the user who must come to terms with it. This is an adaptation of a tale by the Brothers Grimm, in which the user is invited to move back and forth between the webpages, thereby making the experience of the story somewhat non-linear. North Country is a mystery short story about a skeleton, possibly of a woman, found in Upstate New York. The woman, the authorities claim, committed suicide, even though some evidence seems to point to homicide. This type of hypertext is known as a "branching story." Meaning that the user usually has two hyperlinks to select from, but in the end, s/he is expected to visit most, if not all, of the pages to get a handle on the mystery. The Sad Hungarian is the story of a farmer who has lost his wife and is trying to cope with his loneliness and the hard work he must perform day after day. It consists of animated gifs that must be activated by the user with mouse clicks. This story is linear; the user must, however, use the click-back browser button to go back to the main page. And The Story of X is an online collaboration where the user is expected to contribute actual writing. This story is always changing because users are allowed to contribute. The end result of "X" is many entities. The user can navigate the story archive starting with the most recent entries at the top. Unlike the other stories, this one consists of a single page.

The authors treat the web-browser as a direct extension of the printed book, while also experimenting with the possibilities the Internet offers as a creative medium. For example, in North Country the viewer can listen to ambient sound, and in The Grimm Tale each book chapter is accompanied with music compositions and animated gifs. The Sad Hungarian also utilizes animated images-a java applet to be exact, (a small software component that runs in the context of another program, in this case a web browser). (13) Many of these stories, while at times providing options to move back and forth between pages, nevertheless, rely on a linear narrative, and a traditional plot. We can say that they are, in part, an extension of hypertext literature. Most importantly, they point to interests that will be revisited repeatedly by other artists in the years to come. These works are, in essence, remixing pre-existing stories on the web, not to mention the linearity such stories depend on (except for The Story of X, as I explain below). They are what I call selective remixes because they leave the "spectacular aura" (14) of the stories intact.

These early works are historical documents of a transitional period when artists began to explore the paradox of the Internet: while the projects connect us with others in ways previously not possible, they also alienate us from others because such experience is mediated with information. The body is redefined by online communication; (15) the result is work that constantly asks to be completed, or contributed to, by the end user. This preoccupation and constant recall of the body is allegory-a remixed version of what we know in physical space.

|

Helen Thorington and Eric Schefter | North Country: Part 1 | 1996

|

|

For instance, The Grimm Tale and North Country deal with the body in cyberspace. In the former the body of the audience is connected to the young man's when the audience is asked what "to shudder" means to them, and to give feedback through an online form; in the latter the user is asked to identify with a body that is in pieces, which can be read as a metaphor for the fragmentation or reconstruction of one's identity in online communities, and how this is related to physical experience. (16) The story opposes the passive approach to traditional storytelling by constantly posing the question "Who is she?" which, upon closer examination, exposes the impossibility of telling a story that could not be told-how can one tell the story of an unidentified person? (17) This proposition can be read as questioning online identity. Thus, the user ends in a position similar to that of The Grimm Tale. And like The Grimm Tale, North Country has a feedback form for users to contribute their own writings.

This last feature, in fact, is the only thing that The Story of X offers. Here the user is given full license to contribute to the story, making the user (the reader) also the author of the text. This is what I define as a reflexive remix, because the roles of the author and user (reader) are questioned in order to make clear the critical position of this work. (18)

Corporeal experience is a constant preoccupation in the emerging network society; (19) that is how the body is substituted or mediated by information. This is evident in early streaming performances like Finding Time (1999) by Jesse Gilbert and Scott Rosenberg, who organized live sound streams from six continents around the world, with the sole purpose of creating compositions that were mediated by the global network. (20) All of these works depend on a linear narrative that emphasizes and remixes corporeal experience that is then turned into streamed information. Indeed, this preoccupation with disembodiment is still with us today as we look at more recent works like IN Network (2005) by Michael Mandiberg and Julia Steinmetz in which the artists, connected to one another via their cell phones, are always making reference to the body and how it is defined by information. (21)

The early works mentioned above are celebrating the possibilities of the Internet as a viable art medium, and consider the Net an extension of the text. This is true except for The Story of X, as previously noted. These pieces, ultimately, are not legitimized by the fact that they are presented on the net, but by the fact that they make a direct reference to established narrative strategies; and even though they are remixed with options to be experienced somewhat non-linearly, they still hold on to the linear model of storytelling. In the following section we will examine in detail works produced in later years in which Remix is at play, in many ways extending and questioning the early exploration of the works described above.

|

| remixes |

|

remix remix |

|

remezclas remezclas |

|

To better understand Remix, we will compare projects from the Turbulence archive with art from the twentieth century. This will open a window to show how key codes of Remix have been at play under different names throughout history. This section will consider Grafik Dynamo (2005) by Kate Armstrong and Michael Tippett, (22) getawayexperiment.net (2005) by Nathaniel Stern and Marcus Neustetter, (23) The Secret Lives of Numbers (2002) by Golan Levin, et. al., (24) and Grey Area (2002) by Friederike Paetzold. (25)

There are three types of remixes at play today: the Extended Remix, the Selective Remix and the Reflexive Remix. We have briefly considered above how the Selective and Reflexive Remixes are at play in some of the early works in the Turbulence archive. In this section the Selective and the Reflexive Remixes will be defined in direct relation to the visual arts and, most importantly, to recent works in the Turbulence archive. Let us consider the Selective Remix first.

For the Selective Remix the DJ takes and adds parts to the original composition, while leaving its spectacular aura intact. An example from art history in which key codes of the Selective Remix are at play is Marcel Duchamp's Fountain (1917); (26) this work consists of an untouched urinal (save for a traditional artist signature) to reinforce the question, what is art? And codes of a second level remix on Duchamp can be found in Fountain (after Marcel Duchamp) by Sherrie Levine who, in 1991, questioned Duchamp as a man and his urinal as art, leaving intact Duchamp's aura as an artist but not the Urinal's spectacular aura as a mass produced object. (27) In both of these cases there is subtraction and addition (selectively--hence the term, Selective Remixes).

|

left to right

Marcel Duchamp | Fountain | 1917 | image source (26)

Sherrie Levine | Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp) | 1991 | image source (27)

|

|

This strategy became important in the work of pop artists, such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, and is also at play in the online project Grafik Dynamo by Kate Armstrong and Michael Tippett. Like Lichtenstein, who appropriated comic strips for his paintings, Armstrong and Tippett remix comics using RSS technology. They refer to the work as a "live action comic strip" because the panels are updated with new images and caption bubbles every few seconds. The strip re-contextualizes material from Live Journal, an online resource that provides free weblogs to online communities. (28) The Internet user sits back and lets the strips reload information. At one point a caption at the bottom of the far left panel reads "But the journalists asked no questions, and seemed to have been hypnotized," while at the top a small image of Tinker Bell is juxtaposed with the text, "All we need is faith and trust, and a little pixie dust..." On the center panel there is a Jack Daniels bottle and a corresponding thinking bubble that says, "Danger! Sound the whistle!" and the panel on the far right presents a woman wearing a large helmet-like device on her head, and holding a joystick; the speech bubble states, "I would do anything for someone who would fight me!" and the bottom caption reads, "Toy locomotives choked the thoroughfares..."

|

Kate Armstrong and Michael Tippett | Grafik Dynamo | 2005

|

|

All images and text fragments (the latter pre-authored by Armstrong) (29) are combined at random, leaving it up to the user to make sense of them. Grafik Dynamo is a Selective Remix of the traditional comic strip and contemporary culture, with a trace of the postmodern leaning toward fragmentation. (30) The form with allegorical authority is the comic strip, that like the urinal, which once contextualized as a "remix" allows all other forms that come and go to collide, providing multiple significations. Like all contemporary art, this work is not expected to provide specific answers to the viewer, but instead is supposed to provide a space to reflect on the possible meaning of the work of art. Allowing for multiple readings is actually remixed itself by the fact that the project constantly switches images and texts for the viewer in a matter of seconds, presenting compositions which most likely will never be repeated, thus emphasizing the ephemeral experience of the work. Image and text are combined on the panels just for you, and any other viewer who may be accessing the project at the same moment. But that combination will be gone in just seconds, and all that will be left is a memory, a trace. This is a remix because as I previously stated, a remix must leave the aura of the original intact. Grafik Dynamo at no point denies or dares question the authority of the comic strip; if anything, it celebrates it as a tool for cultural criticism and in this way it follows the definition that supports the work of Duchamp and Levine. Duchamp at no point denies the authority of the urinal, but rather uses it to question what is art, while Levine uses the same strategy by making a bronze urinal to question the privileged position Duchamp holds as a man in the artworld, but at no point does she question his status as an important artist. Hence, Duchamp remixes the urinal, while Levine remixes Duchamp.

The same approach is found in getawayexperiment.net by Nathaniel Stern and Marcus Neustetter. The word "remix" is actually used in the description of the work, stating that "they commissioned local sign-makers in Johannesburg, South Africa to 're-mix' five, live websites." (31) This activity is extended to participants online who were encouraged to upload their own images.

|

Nathaniel Stern and Marcus Neustetter | getawayexperiment.net | 2005

|

|

The remixed websites include Joy Garnett's "Solidarity", which also consists of remixes of a painting she created from a photograph, for which she was eventually sued for copyright infringement by the photographer. This remix consists of several pages with variations of the same image, ranging from drawings to pixilated graphics. Another remixed site is "Joburg" a portal to the city of Johannesburg. Hand drawn graphics are presented next to headlines and brief texts making commentaries on the politics of the city. "Google Images" is a third remix in which all images are also hand-drawn, closely mimicking the format found in the actual Google website. "Fox News Channel" is another remix which, like Joburg, makes social comments on news sources. And finally, "Turbulence" a remix of the Turbulence website itself. Here an exact copy of Turbulence's front page is presented, with hand-drawn images and text remixing getawayexperiment.net as well as 1 Year Performance by MTAA. (32)

Like Grafik Dynamo, getawayexperiment.net relies on the spectacular aura of the websites. It is the effective appropriation of their look that gives it authority as a work of art. It can question the validity of these sites, but not the fact that they are "real" sites with cultural agency (just as Duchamp would question art but not what is a urinal, or Levine would question the Urinal and Duchamp as a man, but not Duchamp's authority as an important artist). But getawayexperiement.net also points to the virtual and the physical that is crucial to understanding Internet art as a medium. In fact, the hand-drawn images point to the physical giving way to information online. In this way the hand-drawn activity becomes a footnote-a trace to rely on, like beat juggling becomes a footnote to sampling in the music studio for the DJ producer. Getawayexperiment.net is the most overt selective remix found on the Turbulence website as it deliberately uses remix language to validate its status as a work of art.

|

|

left to right

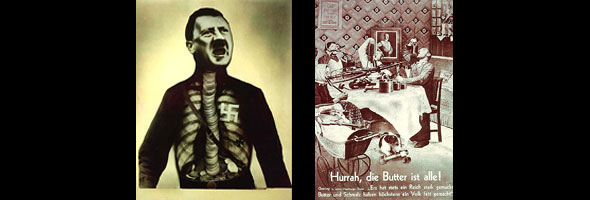

John Heartfield | Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk | 1932 | image source (33)

John Heartfield | Hurrah, the Butter is All Gone | 1935 | image source (34)

|

|

The Reflexive Remix differs in various ways from the Selective Remix; it directly allegorizes and extends the aesthetic of sampling as practiced in the music studio by seventies DJs, where the remixed version challenges the aura of the original and claims autonomy even when it carries the original's name. In culture at large, the Reflexive Remix takes parts from different sources and mixes them aiming for autonomy. The spectacular aura of the original(s), whether fully recognizable or not must remain a vital part if the remix is to find cultural acceptance. This strategy demands that the viewer reflect on the meaning of the work and its sources-even when knowing the origin may not be possible.

An example from art history in which the codes of the Reflexive Remix are at play is the work of John Heartfield, who takes material out of context to create social commentary. His Photo-montages like Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk (33) and Hurrah, the Butter is All Gone, (34) question the very subject that gives them the power to comment. In the former, Hitler, as the title connotes, is presented swallowing gold and is questioned as a leader of Germany; while in the latter, a German family is having dinner, eating military weapons, thus the stability of the home is questioned due to German politics. In his case, the spectacular aura of the source image (like in the second remix) is left intact-but only to be questioned along with everything else: we believe the image but question it at the same time due to the dual transparency of a montage and the realism expected of a photo-image; the work then gains access to social commentary based on the combination of recognizable images.

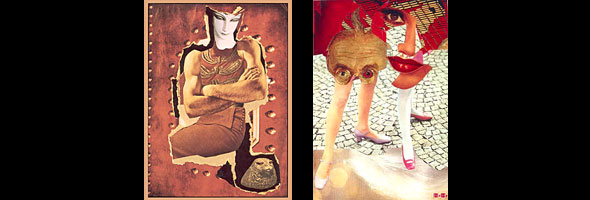

Another example from art history where the codes of the reflexive remix can be found is the work of Hannah Höch. Her collages blur the origin of the images she appropriates; the result is open-ended propositions. Her work often questions notions of identity and gender roles. Yet, even when it is not clear where the material comes from, her work is still fully dependent on an allegorical recognition of such forms in culture at large in order to attain meaning. This is the case in pieces like Grotesque (35) and Tamar. (36) Although they were made 30 years apart, both decontextualze the objects they appropriate. Here we have body parts of men and women remixed to create a collage of de-gendered figures. The authority of the image lies in the acknowledgment of each fragment individually, and a specific social commentary like the one found in Heartfield's work is no longer at play; instead, each individual fragment in Höch's work needs to hold on to its cultural code in order to create meaning, although with a much more open-ended position.

For Heartfield and Höch the subject which gives the work of art its authority is actually questioned; the result is a friction, a tension that demands that the viewers reconsider everything in front of them. This is what makes their art powerful.

|

left to right

Hannah Höch | Tamar | 1930 | image source (36)

Hannah Höch | Grotesque | 1963 | image source (35)

|

|

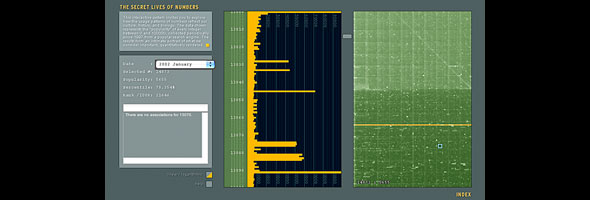

Keeping in mind how the Reflexive Remix works for Heartfield and Höch, we can now examine The Secret Lives of Numbers by Golan Levin, et. al. The work consists of a visualization of numbers and their popularity in culture for the years 1997, 1998 and 2002.

The artists conducted an extensive study of the numbers between one and a million; and put online the visualization of data for one hundred thousand. The reason they give for this is that presenting a visualization for up to a million is not possible online, but they do have an offline installation which presents all the numbers. The data visualization consists of three panels. The first on the far left provides contextual information about the other two. It presents a menu bar that allows the user to choose between the years 1997, 1998 and 2002, and provides him/her with the popularity of the number selected, its percentile, rank and association. The user can choose numbers on the other two panels. The middle panel offers a bright yellow bar-chart at a ninety-degree angle, while the third panel on the right presents a field of green and yellow which varies from lighter to darker values. The color varies with the popularity of the number in culture.

When a number is chosen on either the center or the right panel, the left panel then provides information on that number. While all numbers are ranked, not all of them are associated with an actual activity. Some are, like zip codes, and when you choose a number associated with zips, you get a statement like "Association for 15139: Oakmont , PA." But at times you may receive the statement "There are no associations for number_____" In fact, this is a common result. In the end, The Secret Lives of Numbers takes numbers from the everyday and remixes them as abstraction-which at times can become quite specific as shown above with the zip code association; however, even then the association is a cartographic one (unless you live there), and only points to the activity of measuring. This project is about numerology. In a sense it questions scientific methods of measurement, as the introductory statement reads, "[L]ike every symbiotic couple, the tool we would like to believe is separate from us (and thus objective) is actually an intricate reflection of our thoughts, interests, and capabilities." (37)

The project allegorizes the authority of numbers and the authority of science, yet its aim is not to leave intact our methodology, but rather to bring forth its limitations as a measuring device of human experience. Like Heartfield's Superman, which was conceived to question Hitler as the German leader during WWII, the aim of The Secret Lives of Numbers is to poignantly question the way numbers are seen as "objective" in the world. And to do this effectively the artists appropriate the tools of measurement normally associated with numbers: graphs and charts. The project is a Reflexive Remix because it demands that the Internet user reflect upon and question everything including the authority science normally enjoys, just like the viewer must question the realness of Heartfield's photo-montage.

|

Golan Levin, et. al. | The Secret Lives of Numbers | 2002

|

|

The way we measure ourselves is also the preoccupation of Grey Area by Friederike Paetzold. This project consists of a minimal grey interface offering, once again, the abstraction of numbers. The artist's want (how much the artist desires a non-essential), consumption (how much she is willing to pay) and fulfillment (how much fulfillment she experiences as a result) are presented in three independent charts, and the user is given the choice of accessing the high and low points of the charts in a small window with three scrolling panels. The data can be read quickly as it moves up. The user is also given the choice of viewing the data in three 24 day by 24 hour grids. The user also has the option of turning the grids into three different portraits of the artist, and a final option of combining the three portraits into one. The final combination is accompanied by a soundtrack, also derived from the 24 x 24 hour grids.

This project also questions our relation to measuring ourselves, like The Secret Live of Numbers. This is done by exposing our dependence on a supposed objective method of measurement. The project presents itself as accurate, but there are hints that the interpretation of data is subjective; it is, after all, a "self-portrait." And like The Secret Lives of Numbers it also demands that we rethink our relationship to the tools we use to understand and define ourselves as rational beings. Grey Area, then, is a Reflexive Remix because it takes a person's information and presents it as facts; but the end result is questioned when we try to understand the "portrait" based on supposed accurate data obtained from a subjective self-study. This is similar to the way The Secret Lives of Numbers questions the role of numbers as tools used to accurately measure our reality. In Grey Area abstraction is at play as well; it is not until the three portraits based on the grids data converge as one that the user is able to have a more subjective interpretation of the information in the project. The project is also similar to Hannah Höch's collages in that it takes separate areas that define the human subject and presents them in a way that still does not allow them to gel. While in Höch's work, one is not able to identify the multiple entities that inhabit the collaged bodies, in Paetzold's work the human subject is unidentifiable. A hint of this is given at the end of the piece, when one stops the animation combining all three grids. It reads, "Individuality is resolution dependent."

|

Friederike Paetzold | Grey Area | 2002

|

|

Both The Secret Lives of Numbers and Grey Area present an abstract reading of the human body, and here we find once again the preoccupation with the body giving way to information that was explored earlier in the narratives of Thorington and others. Here the body that was found in pieces like North Country is now comfortably absorbed as pure data, as abstraction. The body has become nothing but numbers that supposedly are factual data. These pieces also share the fragmentation of the body with the works of Heartfield and Höch, because both Dada artists also present bodies or scenes that deny their cohesiveness. Their works pretend to be one when they are many: unified through disunity. They push against the notion of one cohesive body, and instead demand that they be understood as social constructs. It is with Remix as a strategy that the body is referenced over and over in many of the projects found in the Turbulence archive.

To grasp a more precise understanding of how Remix is at play in the Turbulence archive, it must now be defined in detail. Doing this will also enable us to see Remix's role in new media and contemporary culture at large.

|

| loops and samples: the essence of remix |

|

|

|

|

|

The Hip hop DJs improved on the skills previously developed by Disco DJs starting in the late sixties. They took beatmixing and turned it into beat juggling, which means that they played with beats and sounds, and repeated (looped) them on the turntable to create unique momentary compositions. This is known today as turntablism. This practice found its way into the music studio to become part of the tradition of sampling, and has now been extended into the culture at large with the practice of cut/copy and paste.

Loops are also essential to computer technology, for what else does the computer do but execute loops to know what it should be doing at all times? In the days before the first computers, people did calculations manually, but at one point the need to have repetitive computations performed in a more efficient way became a concrete idea. (38) And in 1945, with ENIAC, computers started to take over the role of human computers. (39) The concept of loops played a crucial role in culture at this time, as Pierre Schaeffer and Stockhausen were creating compositions consisting of loops that were performed not by humans but machines. (40) The loop in music became crucial for DJ Culture, as has already been pointed out; and DJ culture would meet digital culture in new media art, in particular Internet art. This merging is crucial to Remix, as I have demonstrated above. Let us now define Remix to understand its complex role in new media art and popular culture.

|

| remix defined |

|

|

|

|

|

To understand the role of Remix in online culture, we must first define it in music. A music remix, in general, is a reinterpretation of a pre-existing song, meaning that the "aura" of the original will be dominant in the remixed version. Of course some of the most challenging remixes can question this generalization. But based on its history, it can be stated that there are three types of remixes. The first remix is extended, that is a longer version of the original song containing long instrumental sections making it more mixable for the club DJ. An example from the history of the DJ would be the work of Jellybean Benitez who became famous for producing and remixing songs for Madonna. (41) The second remix is selective; it consists of adding or subtracting material from the original song. An example of this is DJ producer Todd Terry's 1995 remix of "Missing" by Everything but the Girl. (42) In this case Terry not only extended the original recording, following the tradition of the club mix (like Benitez), but he also created new sections as well as new sounds, while subtracting others, always keeping the "essence" of the song intact. The third remix is reflexive; it allegorizes and extends the aesthetic of sampling, where the remixed version challenges the aura of the original and claims autonomy even when it carries the name of the original; material is added or deleted, but the original tracks are largely left intact to be recognizable. An example of this is Mad Professor's famous dub/trip hop album No Protection, which is a remix of Massive Attack's Protection. In this case both albums, the original and the remixed versions, are considered works on their own, yet the remixed version is completely dependent on Massive's original production for validation. (43) The fact that both albums were released at the same time in 1994 further complicates Mad Professor's allegory.

Allegory is often deconstructed in more advanced remixes following this third form, and quickly moves to be a reflexive exercise that at times leads to a "remix" in which the only thing recognizable from the original is the title. But, to be clear-no matter what-the remix will always rely on the authority of the original song. The remix is in the end a re-mix-that is a rearrangement of something already recognizable; it functions at a second level: a meta-level. This implies that the originality of the remix is non-existent, therefore it must acknowledge its source of validation self-reflexively (even when it is a selective remix). In brief, the remix when extended as a cultural practice is a second mix of something pre-existent; the material that is mixed for a second time must be recognized otherwise it could be misunderstood as something new, and it would become plagiarism. Without a history, the remix cannot be Remix. (44)

The three definitions of Remix presented above extend to visual culture with great efficiency. Some of the key codes of the Selective and Reflexive Remixes had been at play in visual culture for sometime before the DJs experimented with them in the music studio (We saw this in the historical examples I provided of Duchamp, Levine, Heartfield and Höch); but the Extended Remix is not found in popular culture before the 70s, and it actually is not found outside of music. The Disco DJs, going against the grain, actually extended music compositions to make them more danceable. They took 3 to 4 minute compositions that would be friendly to radio play, and extended them as long as 10 minutes. (45) In the seventies this was quite radical because in fact, it is the summary of long material that is constantly privileged in the mainstream-which is true even today. The reason behind this tendency has to do in part with the efficiency that popular culture demands. That is, everything is optimized to be quickly delivered and consumed by as many people as possible-music on the radio is no exception. An obvious example of this tendency is the popularity of publications like Reader's Digest, which offer condensed versions of books as well as stories for people who want to be informed but do not have the time to read the original material, which is often more extensive. (46)

Another recent occurrence that is now emerging on the web is the two-minute "replay" available for TV shows like "Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip." (47) If you missed the show when it aired, you can spend just two minutes online catching up on the plot; in essence, this is a more efficient version of Reader's Digest for TV delivered to your Internet doorstep. The implications that this development has in Remix are closely tied to political economy, and cannot be analyzed at any length in this essay (mainly because of space); however, the Extended Remix must be mentioned because it is actually the foundation of the other two remixes which have been analyzed here. Both the Selective and Reflexive Remixes depend on the efficiency that made mass media powerful-they appropriate this very element to critique the media. They deliver material with the same efficiency and the same expectations of immediate recognition that the culture industry expects. The Extended Remix must also be mentioned because it was the first type of remix in DJ Culture that gave DJs their independence as powerful music producers, at least in NYC.

In the previous sections I analyzed works in the Turbulence archive according to the Selective and Reflexive Remixes, to understand how they attain agency in culture based on an allegorical trace that goes back to the postmodern period. And the definitions presented in this section enable us to understand their extension in culture.

|

| bonus beats |

|

|

|

|

|

It can be argued that the works analyzed so far could slip away from the definitions of Remix I have introduced. However, these definitions are based on the tendencies found in the works themselves. As I have shown, it is the artists' choices, whether they are aware or not, to emphasize criticism with the use of selectivity or reflexivity; and if we are to study how critical practice has developed not just in art, but in culture at large, we can notice that criticism has often taken these two forms. The critic can reflect upon a specific aspect of the work, as in Grafik Dynamo in which the artists have to leave the spectacular aura of the comic strip intact to make social commentary, or bring into question everything, including the methodology that validates the work as in The Secret Lives of Numbers. But this does not mean that the Selective and the Reflexive Remixes cannot be remixed with each other. However, I cannot think of an example in the Turbulence archive that does this. This may not be the case when the Extended Remix is brought into play in combination with either of the other two, but such analysis is also not possible with the works found in the Turbulence archive.

Another argument that can be made is that Remix has been around way before DJs started to develop their compositions in the 70s, so why call the work made after the seventies that use the strategies of Heartfield, Höch and Duchamp "remixes?" The answer to this lies in the action that was performed by DJs, which is now found in the new media user. What the DJ did is s/he stopped the record and played with it as an instrument to create ephemeral experiences that could certainly be recorded, but which did not lose their power of representation. After each performance, the record was left as it was originally made, with obvious wear and tear, of course. The record, in terms of its future access was essentially the same after each performance. It was like a database ready to be accessed again. This is the case with all of the works that have been examined in this text, they are all ready for access from a database, and the user can "play" them, like the DJ would play records. Of course the online user, by default, does not have the same ability to alter the work as the turntablist does, given that the turntablist is essentially a hacker, but the argument here is that all of the works mentioned here can function without having the actual information lost (unless the record is scratched or the server storing the net art files crashes). To understand this, let's consider a Hannah Höch collage once again. Each of the fragments that she uses in her compositions come from a work that she destroyed by cutting a piece out to make it part of her collage. She cannot go back to that image from which she took the fragment and use it in its original form, because it now has some information missing (she cut not copied). In new media, with cut/copy and paste, the artist has the ability to sample without worrying about destroying the file from which the information was taken. Further the user who views the work understands this and knows that the copy being viewed can be accessed in the same exact way, like a record would (this is true even for new media projects, like Grafik Dynamo, which uses randomness with exactitude to present the illusion of chance to create a supposed unpredictable narrative: while text and image may not be repeated together, the algorithm presenting unrepeatable material is repeated perfectly. This type of "collage" that makes new media work possible is completely dependent on sampling, and as I have demonstrated above, sampling is the essence of Remix. This means that while Höch, Heartfield and Duchamp shared elements of remix, their works were not remixes in the way Remix has been defined in this text with the works of Armstrong, Tippett, Stern, Neustetter, Levin and Paetzold. During their times, their works were called readymades, photo-montages and collages because the technology at that time allowed for sampling described by such terms. The basic elements of Remix found in Analog technology (the vinyl record), however, as I have shown, were already at play in their works with great accuracy.

When considering all the variables discussed in the last sections, Turbulence's contribution to the arts and culture at large becomes apparent, and knowing that Turbulence holds a vast amount of valuable remixes makes the project (Turbulence is a project of the organization New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc.) a vital resource to study and enjoy new media. The Turbulence archive must be treasured in the years to come, because in it we can find the first manifestations of this already rich history, pointing to a future that only we can define, a future that, with a critical methodology, can only be promising.

Eduardo Navas.

Eduardo Navas is an artist, historian and critic specializing in new media; his work and theories have been presented in various places throughout the United States, Latin America and Europe. He has been a juror for Turbulence.org in 2004 and for Rhizome.org in 2006-07, New York. Navas is founder and was contributing editor of "Net Art Review" (2003-05), is co-founder of "newmediaFIX" (2005 to present) and is co-founding member of " acute.cc", an international group of artists and academics who organize event and publications periodically. Currently, Navas is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Art and Media History, theory and Criticism at the University of California San Diego. www.navasse.net

|

|

NOTES:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|